In Like a Lion, Out Like a Lamb: Brexit Saga Winds Down

AFP/Getty Images

Elizabeth Tower, usually referred to simply as “Big Ben”, reflected in a puddle. Is it a metaphor for Britain’s post-Brexit fate? It very well could be. Photo Credits: Isabel Infantes/AFP via Getty Images

LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM—The sordid four-year national drama that saw three brutal elections and felled two Prime Ministers has finally come to an end, as Brexit—the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union—officially arrived at 23:00 GMT on January 31. Over the past few weeks, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s formal Withdrawal Agreement has passed through both Houses of Parliament as well as the European Parliament, paving the way for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union and enter a transition period that will last until the end of the year.

For many Britons, the moment stung of anticlimax. Four years of constant wrangling has left the country electorally fatigued, and the celebrations planned by the Conservative government to mark the withdrawal were largely muted. In London, activists joined hands and sang “God Save the Queen”; Big Ben, currently under renovations, stayed silent. Miles to the north, in Edinburgh, Scottish voters held solemn vigils and sadly mourned the end of an era.

How did we get to this point?

Since its inception in 1951, the European Union—then the European Steel and Coal Community (ECSC) and the European Economic Community (EEC)—has always received a cold shoulder from the British. Designed to tie together the economies of Europe so as to render future world war “not only unthinkable but materially impossible”, Germany and France integrated their industrial production, in particular their coal and steel markets, under a single authority. The United Kingdom, preferring to nurture its “Special Relationship” with the United States, stayed pointedly aloof for years.

When the United Kingdom at last tried to join the EEC in 1963, French President Charles de Gaulle infamously vetoed their application with the single word “non”, which came to summarize the continental European outlook towards Britain for many years. Eventually, after de Gaulle’s death, the United Kingdom applied again and was awarded membership in the EEC in 1973, as well as the full European Union when it was created in 1993. Yet they still maintained an independent streak, refusing to join the Schengen Area in 1995 (allowing free travel across EU borders) or the Eurozone in 1999 (establishing a single currency, the euro, which the British eschewed in favor of their pound sterling).

In the early 2010s, those nationalist and isolationist tendencies erupted with the Eurosceptic, or Brexit (a portmanteau of “British exit”), movement, calling for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union. Most of the entrenched establishment across both major political parties, Conservative and Labour, supported remaining in the European Union. Nonetheless, the new pro-Brexit United Kingdom Independence Party, or UKIP, advanced on the Conservatives’ right flank in the 2015 national election, peeling away a considerable amount of votes.

While the Conservative Party still managed to win that election with 330 of 650 seats, their leader and Prime Minister David Cameron was keen to recapture Eurosceptic voters. In an attempt to pacify the dissenters and consolidate right-wing support, Cameron agreed to call a referendum in 2016. He had reason to be confident in voters’ good sense; after all, he had gambled with referendums before in 2014 with Scottish independence, and won a smooth victory that kept the rebellious region in the United Kingdom. Brexit seemed like it would be no different, and so in July 2016 voters headed to the polls to decide the issue. Polls projected it would be a close vote, but ultimately the Remainers would prevail.

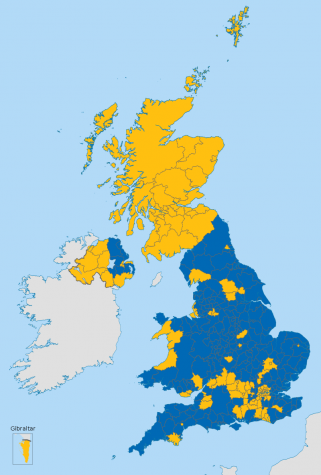

Instead, the shocking result was a 52%-48% vote in favor of Brexit with a high 72% turnout, shattering the national mood. In an eerily prophetic parallel to the 2016 United States presidential election held a few months later, nationalist populism had triumphed in an upset victory over the globalist establishment. Few had expected the Euroskeptics actually to win; not even Nigel Farage, the leader of UKIP, had dared to predict a victory. Across the world, financial markets plunged, with the British pound dropping 8% in a single day and reaching its lowest-ever value against the dollar.

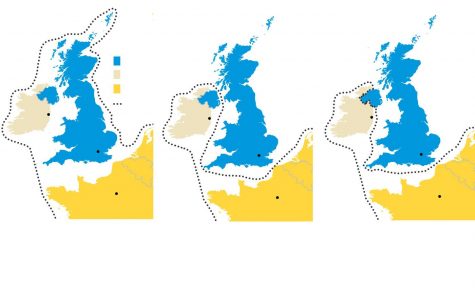

To complicate matters, the issue boiled over into constitutional tensions. The Brexit vote was clearly along regional lines—Scotland, Northern Ireland, and London had voted overwhelmingly in favor of Remain, while the rest of England and Wales were staunchly pro-Leave. Scotland’s narrow 2014 vote to stay in the United Kingdom was shaped in no small part due to the advantages of staying in the European Union, and immediately after the results the leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP), Nicola Sturgeon, demanded a second Scottish independence referendum, so that Scotland could potentially rejoin the EU on her own terms.

An even thornier issue was Northern Ireland, which shares a land border with Ireland, a EU country. For decades since Ireland’s independence in 1922, Northern Ireland was a battleground between loyalists to the British government and republicans who advocated full union with the Republic of Ireland. The Troubles, as they were called, saw ugly fighting along ethno-religious lines and resulted in thousands of deaths. The Good Friday Agreement in 1998 saw a fragile peace restored, but the issue threatened to rear its head again following the possibility of a new border erected between the two halves of Ireland again. There was even wild speculation that London might leave and become its own independent city-state. The prospect of the United Kingdom dissolving suddenly became very real.

The situation grim, Cameron resigned in disarray, and was succeeded as Prime Minister by his Home Secretary, Theresa May. Declaring that “Brexit means Brexit”, May committed to following the will of the people despite having campaigned for Remain in the leadup to the referendum. After preliminary negotiations with the European Union, May formally invoked Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union on 29 March 2017, officially setting into action the legal proceedings of the withdrawal. In an attempt to further strengthen her hand, May called a snap election a month later on April 19 2017, hoping to win a greater majority in the Brexit negotiations.

It turned out to be one of the biggest blunders of modern British politics. In a frazzling election disrupted by two major terrorist attacks in Manchester and on London Bridge, May managed to beat out the curmudgeonly Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn with 317 to 262 seats out of 650, but ended up gambling away the thin majority which she inherited from Cameron. She was forced to form a confidence and supply deal with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland, a humiliating blow that ensured every Brexit deal she put before Parliament would be vigorously contested. Far from strengthening her hand, she had gravely weakened her negotiating position both with Parliament and the European Union.

Nonetheless, May plunged into discussions with the European Union. As time dragged on, the issue became clear: the United Kingdom wanted to have full and sovereign control over her own borders and trade policy, but Ireland continued to get in the way. Both sides agreed that a border would not be constructed between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Yet if the border between the European Union and the United Kingdom were to be drawn elsewhere, the United Kingdom protested, as that would wind up separating Northern Ireland from the rest of the United Kingdom. For months, the fundamentally contradictory three demands fruitlessly grated against one another.

In the end, after a year of negotiations, May managed to agree on a draft withdrawal agreement on 13 November 2018. The temporary solution they agreed to on Ireland was a so-called “backstop” which would activate as a safety net, keeping Northern Ireland within the EU market until a satisfactory deal was reached. Critics bemoaned the decision as simply kicking the issue down the road indefinitely, and thus not really being a solution for anything. Moreover, she apparently had no plan in case the talks broke down, which would result in so-called “no deal Brexit”; such a nightmare scenario would be disastrous for both Britain and Europe’s economies.

When word of the plan (or lack thereof) broke out, May was hounded in Parliament—first the May Government was found in contempt of Parliament on 4 December 2018 for failing to provide legal advice before Parliament, an unprecedented humiliation for a sitting government. In the same month, she suffered two votes of no confidence, both from the opposition benches and from within her own party, each of which could have toppled her from power. May barely survived to fight on, but the worst was yet to come.

The first reading of the bill, on 15 January 2019, resulting in the largest majority against the government ever in British history, with 432 Nays against 202 Ayes. Weeks later, on 12 March the second reading was a slightly less disastrous 392 against 242, but any hope of May’s deal passing was thoroughly crushed when the third reading on 29 March racked up a 344-286 defeat. Three times May had tried to pass the Brexit deal, and three times she had been rejected; roundly battered, there was only one thing left to do. Roundly battered, May offered her resignation in May 2019, curtly saying she was not the right person to lead negotiations.

Brexit had claimed its second Prime Minister as victim, and the race was on to replace her. By July, the Conservative Party had narrowed its selection down to Jeremy Hunt and Boris Johnson, May’s current and former Foreign Secretaries; Johnson had resigned in October 2018 over the Brexit deal, which adroitly positioned him to claim the mantle of the Brexiteers and seize the premiership in a landslide party-wide election. By a vote of 66% to Hunt’s 34%, Johnson won control of the Conservative Party and thereby vaulted to 10 Downing.

Johnson bounded onstage with an immediate constitutional crisis; in a move aimed at limiting the amount of time his opponents in Parliament had time to maneuver around his Brexit policy, he asked the Queen to prorogue, or suspend, Parliament on 10 September 2019. Critics immediately howled that it was a nakedly transparent attempt at circumventing Parliamentary oversight of Johnson’s Brexit plans, and the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom decisively struck down the prorogation on 24 September.

Suffering further blows after a series of defections from his ranks, including prominent members of the Conservative Party like former Chancellors Kenneth Clarke and Philip Hammond, Johnson lost his working majority in Parliament. He was forced to ask for another extension from the European Union, moving the date for Brexit to 31 January 2020. Out of options, Johnson resorted to the tried and true approach: a snap election.

In many ways, the December 2019 elections represented the final struggle in British politics between the Remain and Leave camps. Having culled dissenters from his ranks, Johnson embraced a hardline Eurosceptic policy and a slogan to “Get Brexit Done!” On the other hand, the Labour Party ran the same playbook as they had in 2017, emphasizing domestic issues such as healthcare and the environment and waffling on Brexit. The Liberal Democrats, a minor third party, were the only major party to endorse a reversal of Brexit, while the Scottish National Party once more backed another independence referendum.

Exhausted by three years of bedlam, on 12 December 2019 voters across the United Kingdom delivered the Conservative Party an overwhelming landslide victory, scooping up 365 seats out of 650, their largest since 1987. Labour suffered its worst defeat since 1935, with only 202 seats, and the collapse of its “red wall” in the Midlands and Northern England; the Liberal Democrats underperformed their sky-high expectations with only 11; and the Scottish National Party racked up 48 out of the 59 seats in Scotland. With Johnson having bent the party to his will and smashed his opponents in the polls, Brexit had at last trailed to a coda.

And so, as the clock ticked down on the 31 January deadline when Britain was due to leave the European Union, the national mood turned elsewhere. Attention focused instead on the American airstrike on Qasem Soleimani; the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China; and the Duke and Duchess of Sussex having a spat with the royal family, ironically nicknamed the “Megxit”. While Brexit had roared in like a lion, it went out like a lamb, with neither pomp nor circumstance. Three years of torturous tumult had drawn to an end, and Britons, it would seem, have grown tired and would do anything—anything—to have the coup de grâce delivered.

Yet in many ways this marks only the beginning of a new chapter. The unforeseen consequences of the 2019 election are still rippling; both Labour and the Liberal Democrats are in disarray, with their leaders resigning. How those parties choose to remake their identities will be pivotal questions of the coming decade. The threat of Scottish independence looms again, as the SNP flaunts its victory and mulls trading one union for another. And at the end of the year Britain and the European Union will again be confronted with the headache that has merely subsided and is nowhere close to being cured, when the transition period ends and Britain is truly out in the wilderness.

Vincent Jiang is currently a senior at West Morris Central High School and President of Journalism Club. Passionate about global affairs, he enjoys writing...