The College Admissions Crisis

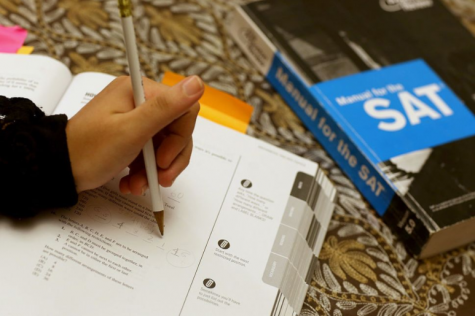

As students progress through high school, many are thinking about senior year and college admissions. In many cases, getting into a good college is the key to a successful career, which makes the admissions process that much more difficult and stressful. This stress is made worse by the fact that the college admissions process is flawed in many ways and often discriminatory towards marginalized groups of students. According to a 2019 poll conducted by USA Today, fewer than 1 in 5 Americans believe that the college admissions process is “generally fair” and about ⅔ of the interviewees described the current process as “[favoring] the rich and powerful.” This issue was highlighted in 2019 when a major college admissions scandal was brought to light. According to NPR’s Elissa Nadworny, this scandal centered around college counselor Rick Singer, who “made millions by bribing coaches at major universities to admit his clients’ children as athletes for sports they often didn’t play, and by rigging SAT and ACT test scores.” The case saw the prosecution of many well-known celebrities including actress Lori Loughlin and realty CEO Robert Flaxman, among others. This scandal really brought to light the way that rich and powerful people can buy their way into success, while less privileged students have to fight much harder for their spot in a prestigious university.

Beyond the obvious bribery, there are other more subtle ways that the college admission process discriminates against lower-income students. “The FBI said this scheme amounts to a ‘rigged system,’ but the truth is that the whole system of college admissions is rigged in favor of the wealthy,” Richard V. Reeves, senior fellow of economic studies at the Brookings Institute, told CNBC. Students from high-income families are more likely to have access to higher-level classes, private tutors, prep classes for standardized tests, and expensive extracurriculars such as musical instruments and club sports. Lower-income students are more likely to have to work in order to sustain their family economically, which takes away from the time that they could be studying or preparing for the college admissions process. In fact, according to Harvard Professor of Economics Raj Chetty, students from the top 1% of Americans are 77 times more likely to be admitted to an Ivy League college than students whose families make less than $30,000 a year.

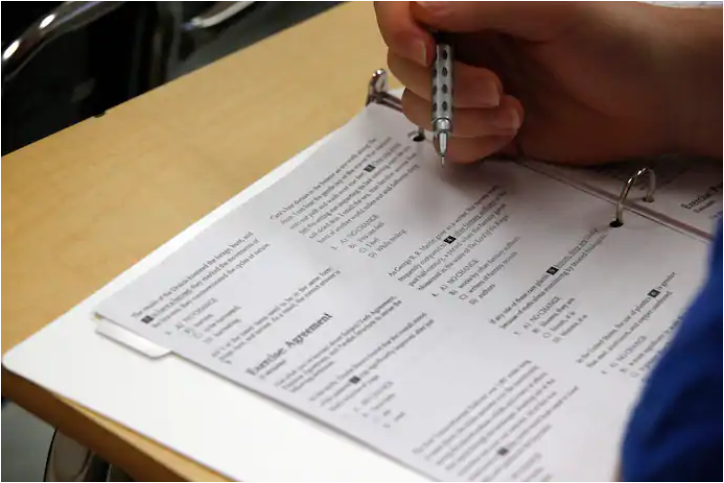

There have been numerous attempts to alleviate this economic divide, including the expansion of AP classes to lower-income students and the College Board’s initiatives to create an “adversity ranking” which would make colleges more aware of the adversity that students faced during their years in high school. Both of these initiatives did very little to solve the problem, however. In theory, expanding AP classes to lower-income school districts would make it easier for students in these areas to get into better colleges. Unfortunately, this does not pan out as cleanly. Although these students now have access to AP classes, most of them cannot afford to take the costly AP exam, and even fewer pass. In 2016, over 70% of African-American students and 57% of Hispanic students did not pass their AP exams, compared to a national failure rate of 42%. Because a large percentage of lower-income students are African-American or Hispanic, this points out a concerning trend of failure that has not yet been addressed by the College Board, who administers the AP tests.

College Board’s other initiative, the “adversity ranking”, also didn’t end up working out very well. In order to determine this ranking, the College Board used national statistics on crime, education, poverty, and many other factors to determine a “score” for each student. This system is deeply flawed. A student can live in a high-income neighborhood but still face serious family issues at home that prevent them from success, while another might live in a low-income neighborhood but still be well-off financially. In both cases, the student has been improperly “scored.” Both of these issues highlight the fact that although steps have been taken to try and alleviate this massive economic disparity in college admissions, the process is still inherently biased towards higher-income students and is in need of serious reparations. These reparations would likely take serious time and effort from multiple areas as this issue can’t be solved with just one piece of legislation or mandate towards colleges. It is simply a smaller facet of the larger issue of systemic poverty. Impoverished students aren’t simply turned away because they can’t afford to take AP classes, they’re also more likely to have obligations in their life that are more important than education. Until our society fully addresses the problem of systemic poverty and classism in the United States, there’s a very low chance that we will see an equal opportunity college application system in the future.

Evelyn is a senior and Journalism III student this year, and is one of The Paw's editors-in-chief for two years running! This year she is excited about...