The Model Minority Myth, and It’s Effect on the Current Racial Climate

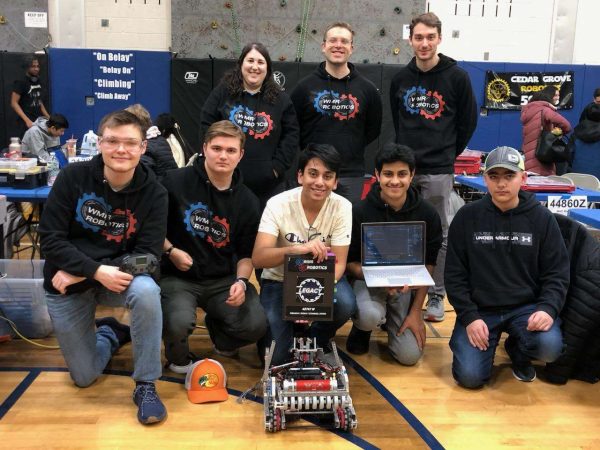

A “Stop Asian Hate” rally in Boston this March.

Recently, the news has been awash with stories about violence against Asian-Americans. From the Bay Area attacks on Asian-American elders during Lunar New Year to the recent shooting in Atlanta, anti-Asian sentiments have only grown since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus. Many have been quick to call Asian-Americans sick “disease-spreaders,” and it has catalyzed the rise of violence against Asians in the US. But this isn’t a new problem. It’s a very visible symptom of a disease that has infected this country since the beginning.

Violence against Asian-Americans has had a long and detailed history in the United States. From the 1871 massacre of Chinese-Americans in Los Angeles and subsequent Chinese Exclusion Act to the Japanese internment during WWII, and now the heightened tension due to COVID-19, anti-Asian sentiments have been present in the US since its inception. And yet, for all the discrimination and racism that is faced by Asian-Americans today, they are often left out of the discussion entirely. Model minority myths, propagated to turn minority groups against one another, have led to the stereotype that Asians are universally successful and hardly minorities at all. They receive the bad parts of being a minority here in the US: the racism, bigotry, and discrimination, but are often held to a higher standard, not allowed to complain about their problems due to the stereotype of quiet success.

Being stereotyped as universally successful isn’t beneficial. It washes over all of the problems faced by Asian-Americans in this country, and often causes more problems than it solves. The recent lawsuits against Harvard University, for example, argue that Asian students are held to a higher standard, and often need much higher standardized testing scores and grades than their white counterparts in order to be accepted. Just like the oft-used saying “all Asians look the same,” the Asian-American community is seen as a monolith, a homogeneous group of hard-working people who have overcome every obstacle to achieve career success, often in fields like medicine and research. But this myth ignores the diversity of the community, both culturally and socioeconomically, and often glosses over the disadvantages of less successful Asian Americans.

And in this way, Asian Americans are stuck at a crossroads. They’re your Japanese spies and job-stealing foreigners, too alien to be true Americans, but they’re also your doctors and businessmen, too successful to complain about their station. In reality, racism and discrimination towards Asian-Americans is nowhere near new. But they’re expected to be the silent and successful minority and dissuaded from making a fuss about discrimination, from sources both inside and outside their community.

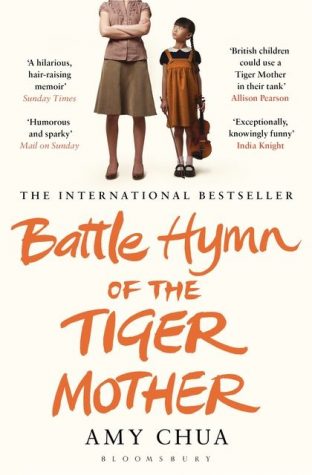

Because the Asian-American community must look inwards as well. The idea of the model minority has permeated the mindset of many in the community itself, and it is spread throughout from parents to children. Take the book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother by Amy Chua. In the popular 2011 release, Chua, a Yale professor of law, criticizes western parenting styles and emphasizes the efficiency of Chinese parenting styles, which in her case include verbal abuse and harsh punishments. Whether intentionally or not, Chua takes advantage of the model minority stereotype. Her assertions that Chinese parenting is superior to western and breeds success, as well as her standing as a distinguished professor of law, promotes the idea that Asian-Americans are an inherently successful minority group. It can cause many Asian-American students to face harsh pressure from both their parents and themselves, worried that they won’t live up to expectations if they don’t do well in school.

It’s worth noting that the Asian-American community isn’t the only minority group affected by the model minority myth. The model minority myth is used in order to split minority groups in the United States and keep both groups down. In order for there to be a model minority, there must be another lesser group as well, and in the United States this stereotype falls on Black Americans. . Black Americans are told that they complain too much, that they should look to Asians as the way to be a good minority in the United States. Poor Asian immigrants often can only find homes in minority communities, where tensions between different groups arise. In order to fully support both communities in their quest for equality, the model minority must be fully debunked for what it is, a myth.

Even though it’s a myth and a stereotype, the idea of the model minority is a large part of the surge in violence against Asian-Americans that we’re seeing now. People everywhere, although most notably in the United States, have been quick to blame the Chinese for spreading COVID. All Asians have been affected, told to “take the disease back to Asia” and go back to their countries. The Stop AAPI Hate National Report recorded almost 4,000 hate incidents against Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders from March 2020 to February 2021. Verbal harassment made up 68.1% of incidents, while physical assault made up 11%. That’s more than 400 counts of physical assault in the past year, and these are only the incidents that were reported. About 68% of respondents were women, which fits with the stereotype that Asian-American women are petite, docile, and unlikely to make a fuss, making them easier targets in the minds of racist, ignorant attackers.

Stop AAPI Hate recorded instances of assault, both physical and verbal, and it’s disgusting the way that people act in these situations. Asian-Americans record getting spit on, called numerous racial slurs, being barred from establishments, and in one instance in California, having a car drive directly into a crowd of protesters. In one situation more close to home, an Asian-American living in Randolph was sent messages telling them to “go die in Wuhan, China, the origin of the coronavirus and take Trump with you! B*TCH!” The coronavirus has allowed racists and bigots in this country an excuse to act on their prejudices, and the fact that it’s only becoming big news after a mass shooting is frankly sad.

There’s one more thing to address: allyship with the Asian-American community. In the past year, allyship has become a hot topic of discussion. Topics like performance activism were heavily debated earlier in 2020 during the BLM protests, and they’re coming back under fire now. And it’s an important distinction to make. You can’t sit back and be a bystander to blatant racism and then call yourself an ally by posting meaningless hashtags on social media. The only way to actively combat racism is to be anti-racist. It might be uncomfortable to confront friends or colleagues about their racist behavior, but then don’t turn around and think you’re a proper ally. Real change is made through action, not just posting two pictures and then patting yourself on the back. Change is hard, but the stress and suffering faced by the Asian-American community this past year is harder. It is sometimes necessary to make sacrifices for the good of greater society, and this is a prime example.

Evelyn is a senior and Journalism III student this year, and is one of The Paw's editors-in-chief for two years running! This year she is excited about...